Problem logging into the journal panel

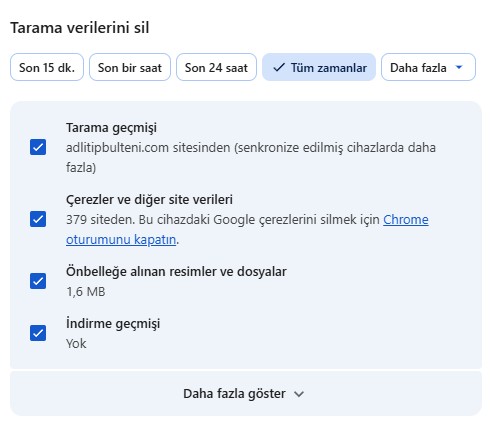

Authors experiencing issues accessing the journal dashboard should clear their browser cache. For example, in Google Chrome, press the SHIFT, CTRL, and DELETE keys simultaneously. In the "Delete Browsing Data" window that appears, select "All Time." Check the "Cookies and other site data" box, and click the "Delete data" button to refresh the browser's cache.

Read more about Problem logging into the journal panel